How Effective is Pension Fund Governance Today, and Do Pension Funds Invest for the Long Term? Findings from a New Survey.

We need to move from long-term investing solutions to actions…….. First, we need to address the issue of governance of financial institutions.”

Angel Gurria - General Secretary - OECD

Background to this Study

This study marks the continuation of a series of survey-based research projects on pension fund governance by the authors and colleagues that stretch back over 20 years. A catalyst for this new effort was the Focusing Capital on the Long Term (FCLT) initiative launched by Dominic Barton (McKinsey) and Mark Wiseman (CPP Investment Board) in 2013.i In a subsequent Harvard Business Review article that provided context for the FCLT initiative, they wrote:

“If asset owners and managers are to do a better job of investing for the long-term, they need to run their organizations in a way that supports and reinforces this.”ii

Obviously, the quality of the governance function in asset owner organizations is critical to this “do a better job of investing for the long-term” quest. Given our prior survey experience in the governance area, we offered to update our work in support of the FCLT initiative, and at the same time, gain a better understanding of the degree to which pension funds actually practice ‘long-termism’ in investing. We sent out a survey in June 2014 to 180 CEOs (or equivalents) of major pension (and related) organizations around the world. The survey’s governance component was identical to prior surveys sent out in 1997 and 2005. Two months later we began the work of analyzing the 81 completed surveys, comparing the 2014 governance-related responses to those provided in 1997 and 2005, and interpreting the responses in the long-term investing part of the survey. This paper sets out our findings, and their implications for raising the effectiveness of the governance and investment functions of pension (and related) organizations.

Organization of this Paper

The paper is organized into six parts:

Part I: Study Summary and Conclusions

Part II: Key Findings from Prior Governance Research

Part III: Description of the 2014 Survey and the Survey Respondents

Part IV: 2014 Survey Findings on Governance

Part V: 2014 Survey Findings on Long-Term Investing

Part VI: Key Take-Aways from the 2014 Survey Findings

About the Authors

Keith Ambachtsheer is Director Emeritus of the International Centre for Pension Management (ICPM) and Academic Director of the Rotman-ICPM Board Effectiveness Program at the Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto. He is co-founder and President of KPA Advisory Services, and co- founder and Board Member of CEM Benchmarking Inc.

John McLaughlin is co-founder and Board Chair of CEM Benchmarking Inc. He is also a Board Member of a number of public and private enterprises and a graduate of the ICD / Rotman Directors Education Program and a holder of the ICD.D designation.

Part I: Study Summary and Conclusions

We recently conducted a survey-based study on the effectiveness of pension fund governance, and on long-horizon investment attitudes and practices. A broadly-based group of 81 major pension organizations from around the world with aggregate assets of USD $5 trillion participated in the study. Here we set out the major study findings.

On Pension Fund Governance

Prior studies on the effectiveness of pension fund governance over the course of the last 20 years all reached the conclusion that there was considerable room for improvement. Despite evidence that board effectiveness is marginally improving, our survey-based study conducted in 2014 finds that much work still needs to be done:

- Board selection and improvement processes continue to be flawed in many cases.

- The board oversight function in many organizations needs to be more clearly defined and executed.

- Competition for senior management and investment talent is often hampered by uncompetitive compensation structures.

It will require a concerted, ongoing joint effort by pension plan stakeholders, pension organization boards, regulators, and legislators to change the current situation.

On Long-Horizon Investing

There was broad consensus among the survey participants that conceptually and aspirationally, long- horizon investing is a valuable activity for both society, and for their own fund. However, there is a significant gap between aspiration and reality to be bridged. Barriers to putting good long-horizon investing intentions into practice include:

- Regulations that force short-term thinking and acting.

- A short-term, peer-sensitive environment that makes it difficult to truly think and act long-term.

- The absence of a clear investment model, performance metrics, and language that fit a long-term mindset.

- Alignment difficulties in outsourcing, and compensation barriers to in-sourcing.

Here too a concerted effort (both inside pension organizations and among them) will be required to break down these barriers.

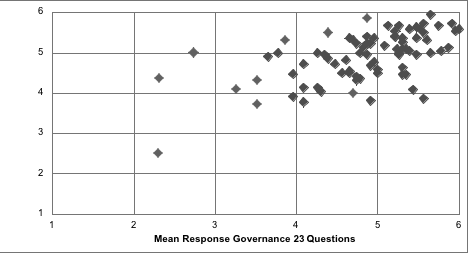

On The Relationship between Governance and Long-Horizon Investing

We found statistically positive relationships between the governance quality rankings and the long-horizon investment quality rankings. This raises the question of causation. Is the measured correlation merely a statistical artifact of the biases of the 81 survey respondents? Or is better governance really driving long-horizon investing quality? The qualitative commentary provided by the survey respondents make a plausible case for the latter interpretation.

Part II: Key Findings from Prior Governance Research

Anthropologists O’Barr and Conley caused quite a stir in 1992 with their book Fortune and Folly: The Power and Wealth of Institutional Investing.iii After observing the behavior of nine major US pension funds over a two-year period, they concluded that the aim of the funds appeared to be focused more on responsibility deflection and blame management than on good governance and creating value for fund stakeholders. This observed behavior is very much in line with Keynes’ 1936 remark about investment committees that “worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally...”.iv

A 1995 study in which we were involved surveyed 50 senior US pension fund executives on what they estimated the “excellence shortfall” to be in their organization. In other words, if the known barriers to excellence could be lifted out of their organizations, by how much might long-term investment performance improve? The median response was 66 bps. When asked to identify the sources of excellence shortfall, respondents most frequently cited poor decision-making processes, inadequate resources, and a lack of focus and clarity of mission.v Studies by Clark et al. in the UK (2006 and 2007) and by Clapman et al. in the USA (2007) confirmed the presence of these challenges in many pension organizations.vi

An article by Clark and Urwin in the inaugural issue of the Rotman International Journal of Pension Managementvii (RIJPM Fall 2008) made these key observations about Boards of pension organizations:

- Understanding human behavior and cognitive biases is an important element in designing effective Board governance structures.

- Board members must be collegial, representative, and make a collective commitment to understand and fairly balance stakeholder interests.

- In reality, Boards often suffer from unacknowledged differences in individual decision-making styles, lack focus, and are overwhelmed by the range of issues they must deal with.

- In this context, the Board Chair role is critically important. The Chair must ensure there is a clear link between stakeholder expectations and the organization’s culture, its strategic plan, and how it executes that plan. Most importantly, this person must command strong personal respect.

An article by Ambachtsheer, Capelle, and Lum in that same RIJPM issueviii describes a pension fund governance survey first carried out by the authors in 1997, and repeated in 2005. Its key findings and conclusions are set out below.

Understanding the Pension Governance Deficit

The survey posed two open-ended questions to pension fund CEOs. One was about Board priorities; the other about organizational priorities. It also asked participants to rank 45 statements about governance, management, and operational effectiveness in their organizations. They were asked to indicate their disagreement/agreement with each statement on a scale from 1 (total disagreement) to 6 (complete agreement). Each statement was crafted so that the higher the assigned number, the greater the perceived effectiveness. The survey elicited 80 responses in 1997 and 81 in 2005 from diverse groups of pension organizations by type, size, and geography.

Table 1 sets out the CEO responses to the Board and managerial priorities questions in the 2005 survey. They saw big challenges for Board governance in three areas: Agency/Context issues, Board Effectiveness issues, and Investment/Risk Management issues. The biggest managerial challenge is strategic planning and its execution. Table 2 provides greater detail about each of these four perceived challenge areas. Note that while, on the one hand, the four areas are distinct, they are also the four key pieces of a larger pension governance and management puzzle. They revolve around the following questions:

- How clear are pension Boards about the pension contracts they are overseeing and about the fiduciary duties of loyalty and even-handedness that oversight involves?

- Does the Board understand the difference between Board governance and management accountability for achieving clearly agreed-on organizational goals? Can the Board ask the right questions about strategy and its execution?

- Has the organization worked out a set of well-articulated investment beliefs that both the Board and management understand and truly believe in? Is it clear which stakeholders are bearing what risks?

- Does the organization have the necessary resources to execute its strategic plan? If not, what are the blockages and what is the plan for removing them?

The relevance and importance of these questions is reinforced by the outcomes of the scoring process of the 45 survey statements. Table 3 compares the six lowest-scoring statements in 1997 and 2005. Note they are almost identical, and that, directly or indirectly, all six relate to Board effectiveness problems. Specifically, they point to Board selection and evaluation difficulties, to ineffective delegation to management, and to attracting and retaining top talent into the organization.

Table 1: Pension Fund Oversight and Management: What Really Matters

|

What are the more important oversight issues? |

Proportion of Responses |

|

a. Agency/context issues b. Governance effectiveness issues c. Investment beliefs/risk management issues |

44% 36% 20% |

|

* Source, RIJPM, Fall, 2008 |

|

| What are the more important management issues? | Proportion of Responses |

|

a. Strategic planning/management effectiveness b. Agency/context issues c. Investment beliefs/risk management issues |

73% 15% 12% |

Table 2: Pension Fund Governance and Management: Specific Challenges

|

1. Agency/Contest Issues 2. Oversight Effectiveness Issues 3. Investment Beliefs/Risk Management Issues 4. Strategic Planning/Management Effectiveness Issues |

Table 3: The Six Lowest Scoring Statements in 1997 and 2005

|

* Source: RIJPM, Fall, 2008 |

|||

|

Ranking |

1997 |

2005 |

Ranking |

|

40 |

Compensation levels in our organization are competitive |

Compensation levels in our organization are competitive |

40 |

|

41 |

My Board of Governors does not spend time assessing individual investment managers or investments. |

My Board of Governors does not spend time assessing individual investment managers or investments. |

41 |

|

42 |

My Board of Governors examine and improve their effectiveness on a regular basis. |

My Board of Governors examine and improve their effectiveness on a regular basis. |

42 |

|

43 |

Our fund has an effective process for selecting, developing, and terminating members of the Board of Governors. |

I have the authority to retain and terminate investment managers. . |

43 |

|

44 |

I have the authority to retain and terminate investment managers. |

Our fund has an effective process for selecting, developing, and terminating members of the Board of Governors. |

44 |

|

45 |

Performance-based compensation is an important component of our organization design. |

Performance-based compensation is an important component of our organization design. |

45 |

Recommendations for Action

Based on these findings, the article identified six opportunities for fixing the documented governance deficit that still existed in many pension organizations in the middle of the first decade of the 21st Century:

- Redesign pension contracts to eliminate any existing incompleteness, over-complexity, and/or unfairness problems. This is usually not something Boards themselves can do, but their views will likely be carefully listened to by the contracting parties.

- Create a Board skill/experience matrix to reflect the reality that while pension Boards need to be seen to be representative and hence legitimate, that is not enough. They must also possess the requisite collective skills and experience to be an effective governance body.

- Initiate a Board self-evaluation protocol in order to identify and address weaknesses.

- Ensure clarity between Board and management roles. Lack of clarity causes organizational gaps, compressions, and a great deal of frustration.

- Adopt a high-performance stance through-out the organization and ensure it has the necessary human and technical resources to turn the aspiration into reality.

- Make Board effectiveness a regulatory requirement. It would be a simple matter for pension regulators to require that pension organizations annual disclose the steps they are taking to ensure that an effective governance function is in place.

A significant outcome of this work was the establishment of the week-long Rotman-ICPM Board Effectiveness Program (BEP) for Pension and Other Long-Horizon Investment Organizations in 2011. Its curriculum covers all six of the ‘action’ opportunities listed above. The Program has been offered five times thus far, resulting in 153 BEP ‘graduates’ from 56 different organizations and 11 countries.ix

Part III: Description of the 2014 Survey and the Survey Respondents

An interesting dimension in the cited 2008 RIJPM article was the ability to compare the assigned CEO scores to the same statements in 1997 and 2005. Based on the average 1997/2005 scores, we found four statements related to strategic planning, Board self-evaluation, and HR/compensation practices showed the greatest improvement over the period. However, Table 3 indicates that these dimensions of pension fund governance and management were still among the lowest ranked among all 45 statements in 2005. The implication was that much work remained to be done.

The introduction to this paper noted that with nine years having passed since the 2005 survey, we decided to conduct the pension fund governance survey a third time in 2014. To focus more directly on Board governance matters, we pruned the 45 original survey statements down to the 23 that focused most directly on the governance function. Once again, we were able to achieve the high response rates of 1997 and 2005. Table 4 compares the demographics of the 2014 responding organizations with those of 1997 and 2005. Note that the 2014 responding group was considerably larger, less corporate, and more geographically diverse than the 1997 and 2005 groups.x Aggregate assets amounted to about USD $5 trillion. Table 5 indicates that the people who completed the survey were generally senior, long-tenured pension organization executives.

Table 4: Demographics of the 1997, 2005, and 2014 Responding Groups

|

Survey Respondents |

1997 |

2005 |

2014 |

|

Number of Respondents |

80 |

81 |

81 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

US |

54% |

44% |

29% |

|

Canada |

46% |

41% |

28% |

|

Europe |

|

11% |

31% |

|

Asia, Australia, New Zealand |

|

4% |

14% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Public Sector |

24% |

41% |

60% |

|

Corporate |

63% |

38% |

19% |

|

Other |

14% |

21% |

21% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Median plan size Billion USD |

2.1 |

3.7 |

22.7 |

Table 5: Demographics of the People Completing the 2014 Survey

29 respondents represent ICPM Research Partners

| Global | Senior |

|

23 Canadian 22 European 25 United States 11 Asia, Australia, NZ |

54 CEO, CIO, Executive or Managing Director 27 Other Senior Titles |

| Long Tenured in Organization | Long Tenured in Positions |

|

Average 12 years with organizations Range 1 to 35 years |

Average 7 years in position Range 1 to 27 years |

Part IV: 2014 Survey Findings on Governance

We explained above that the respondents to the earlier 1997 and 2005 surveys were asked to rank 45 statements about governance, management, and operational effectiveness in their organizations. They were asked to indicate their disagreement/agreement with each statement on a scale from 1 (total disagreement) to 6 (complete agreement). Each statement was crafted so that the higher the assigned number, the greater the perceived effectiveness. As already noted, the 2014 survey was reduced to the 23 statements directly related governance effectiveness. In the analysis that follows, the 2014 responses to these 23 statements were compared to the 1997 and 2005 responses to the same 23 statements.

Insights from the Rankings

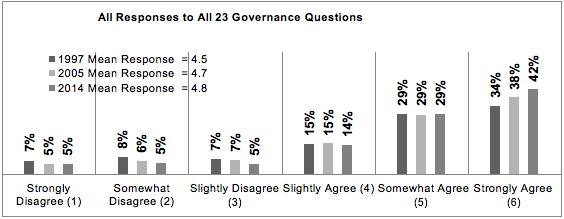

Figure 1 displays the distribution of responses to the 23 governance statements in 1997, 2005, and 2014. The general bias towards high rather than low scores is a common phenomenon with this type of survey design. However, note that the average ranking marginally increased over to the 17-year period (i.e., from 4.5 to 4.7 to 4.8), possibly indicating a marginal improvement in the effectiveness of pension boards over this period.

Figure 1: The Response Distributions in 1997, 2005, and 2014

Table 6 compares the five highest-scoring statements in 2014 (i.e., indicating the highest satisfaction levels) with the five lowest-scoring statements (i.e., indicating the lowest satisfaction levels). Readers are invited to draw their own conclusions from Table 6. It seems to us there are elements of contradiction in these two sets of survey responses. For example, how is it possible for senior executives in pension organizations to, on the one hand, say they are getting the resources necessary to do their job, but on the other, say that compensation levels in the organization are uncompetitive? Similarly, how is it possible for senior executives in pension organizations to say that their Boards hold them accountable for results, but on the other, that they meddle in operational matters (e.g., the hiring and firing of investment managers)?

Table 6: Areas of Highest vs. Lowest CEO Satisfaction

|

Highest Agreement in Latest Survey |

Mean Score 2014 Rank |

| My governing fiduciaries do a good job of representing the interests of plan stakeholders. |

1 |

| Developing our investment policy required considerable effort on the part of myself and the governing fiduciaries and it reflects our best thinking. | 2 |

| There is a clear allocation of responsibilities and accountabilities for fund decisions between the governing fiduciaries and the pension investment team. | 3 |

| My governing fiduciaries hold me accountable for our performance and do not accept subpar performance. | 4 |

| My governing fiduciaries approve the necessary resources for us to do our work. | 5 |

|

Lowest Agreement in Latest Survey |

Mean Score 2014 Rank |

| I have the authority to retain and terminate investment managers. | 19 |

| Compensation levels in our organization are competitive. | 20 |

| My governing fiduciaries have superior capabilities relevant knowledge, experience, intelligence, skills necessary to do their work. | 21 |

| Our fund has an effective process for selecting, developing and terminating its governing fiduciaries. | 22 |

| Performance based compensation is an important component of our organizational design. | 23 |

Table 7 compares the five lowest-scoring statements in 1997, 2005, and 2014. Remarkably, they were the same five each time. To us, they offer the clearest indication of where the challenges with governance in the pensions field continue to lie, and the consequences they continue to lead to. Specifically, inadequate selection processes for board members continue to lead to ineffective board oversight protocols, which in turn continue to lead to board meddling in operational matters, and to inadequate resourcing in such key functional areas as investing.

Table 7: The Five Lowest-Scoring Statements in 1997, 2005, and 2014

|

Lowest Agreement over 3 Surveys |

Mean Score 1997 Rank |

Mean Score 2005 Rank |

Mean Score 2014 Rank |

| Compensation levels in our organization are competitive. | 18 | 18 | 20 |

| My governing fiduciaries examine and improve their own effectiveness on a regular basis. | 20 | 20 | 17 |

| I have the authority to retain and terminate investment managers. | 22 | 21 | 19 |

| Our fund has an effective process for selecting, developing and terminating its governing fiduciaries. | 21 | 22 | 22 |

| Performance based compensation is an important component of our organizational design. | 23 | 23 | 23 |

Table 8 assesses the regional variations in how the 23 statements were ranked. The clear message here is that the European respondents scored a number of governance statements materially lower than their counterparts in North America and the Pacific Rim. At the other end of the spectrum, pension organizations in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand were more likely to feature a performance-based element in their compensation arrangements.

Table 8: Regional Variations in Governance Quality

|

+ Response more than 0.5 above mean |

|||||

|

Regional variation from mean response to questions |

Europe |

Canada |

USA |

Asia Australia New Zealand |

All plan mean response |

|

Performance based compensation is an important component of our organizational design. |

- |

+ |

|

+ |

3.7 |

|

My governing fiduciaries set a clear, appropriate, understandable and well-communicated framework for values and ethics. |

-

|

|

|

|

5.1 |

|

My governing fiduciaries set clear, appropriate, understandable and well communicated standards for our organizational performance. |

- |

|

|

|

4.9 |

|

My governing fiduciaries do a good job of balancing over- control and under-control. |

- |

|

|

|

4.8 |

|

I have the necessary managerial authority to implement long term asset mix/balance sheet risk policy within reasonable limits. |

-

|

|

+ |

|

5.0 |

|

There is a clear allocation of responsibilities and accountabilities for fund decisions between the governing fiduciaries and the pension investment team. |

|

|

|

- |

5.4 |

Additional Insights on Governance from Respondent Comments

In addition to ranking the 23 governance statements, survey participants were asked to address the question: “What do you see as the most important governance questions facing your Board at this time?” This is what they told us:

Board Composition and Skills

- “Our board members should be more experienced and have more skills and ”

- “Getting timely appointments…”

- “Board turnover: too much among beneficiary reps and legislative reps. Too little among appointed investment experts. Control rests with state legislature”

- “Too much board turnover (due to term limits). Too much staff turnover (due to retirements) Even though policies are well documented, the loss of institutional memory and continuity has the potential for negative outcomes…"

- “The most important issue in governance …is illiteracy in committee members regarding pension fund management. Governance is in place but hardly operational…”

- “Selection of pension committee members with sufficient investment expertise …"

- “Education of Board members…”

- “Getting new governing fiduciaries up to speed on pensions, pension investing, and fiduciary management (80% turnover) …”

- “…Ensuring ongoing Board capacity for increasing oversight and risk management .”

- “…Securing the ability of the board to actually handle the (increasing) responsibilities allocated to the board through regulatory changes…”

Board Process

- “The board spends too much time on administrative issues and individual approvals of investments and not enough time on overall strategic positioning of the portfolio and longer-term macro risks and opportunities for the fund and the business. "

- “…blessed with a …truly outstanding group…., but they are collectively flying just above the tree tops instead of a higher fiduciary altitude. … time is largely spent at the deal and manager level…”

- “Refused to delegate manager hiring and firing…”

- “…(Management) can terminate while (Board) Investment Committee retains managers”

- “Time management: spending more time on interviewing and meeting with investment managers versus strategic business decisions… "

- “Staying purposefully high level/ strategic in their decision making and understand/ be comfortable with the importance of clear delineation of responsibilities between the board and the organization…."

- “The board spends too much time on administrative issues and individual approvals of investments and not enough time on overall strategic positioning of the portfolio and longer-term macro risks and opportunities for the fund and the business.”

Compensation

- “The design and implementation of market-competitive compensation plans to attract and retain high-caliber investment and senior management talent. As (a public entity we are) subject to restraint legislation and policies affecting compensation and business-related expenses. “

- “Alternative compensation models: no appetite to review or discuss these."

Clearly, these respondent comments strongly re-enforce the insights extracted from the survey statement rankings.

Part V: 2014 Survey Findings on Long-Term Investing

Consistent with the design of the governance component of the survey, respondents were also asked to rank their agreement/disagreement with 22 statements related to the organization’s attitudes and practices regarding long-horizon investing on a scale from 6 to 1. Below, we report their responses, both to the 22 statements and to our invitation to share any comments they might have on the topic.

Insights from the Rankings

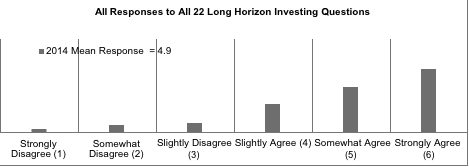

Figure 2 displays the distribution of assigned rankings to the 22 long-horizon investing statements. Note the shape of the distribution is the same as those of the governance quality rankings, with a strong bias towards assigning high rankings. Recall that the average 2014 governance quality ranking was 4.8, almost identical to the average long-horizon investing satisfaction ranking of 4.9.

Figure 2: The Long-Horizon Investment Ranking Distribution

Table 9 shows a strong dichotomy between highly-ranked aspirational statements about long-horizon investing, and the much lower-ranked implementation realities. For example, on the one hand, pension funds seem to have good policy intentions and strong beliefs that long-horizon investing is a potentially promising value-adding activity. On the other hand, survey respondents indicate they have considerable difficulties with such implementation activities as creating proper incentives for long-horizon investing, participating in constructive Environmental, Social, and Governance-related and engagement strategies, and designing effective performance monitoring and measurement systems.

Table 10 provides a geographic breakdown of the long-horizon investing rankings. It shows an interesting contrast with Table 8, which provided a geographic breakdown of the governance quality rankings. Whereas European pension organizations scored lower on a number of key governance criteria in Table 8, they score higher on two key long-horizon investing criteria (e.g., in engagement strategies and in integrating ESG criteria into investment decision-making).

Table 9: Highly-Ranked vs. Lowly-Ranked Long-Horizon Investing Statements

LONG HORIZON INVESTING

| Highest Agreement | Mean SCore 2014 Rank | Lowest Agreement | Mean Score 2014 Rank |

| We believe that the capability to invest for the long-term is a significant advantage in creating value. | 1 | We (or our managers on our behalf) have explicit policies for engaging corporations (or other organizations) we invest in when we think proactive engagement is warranted. | 18 |

| Our organization’s statement of investment policy explicitly states that we invest for the long-term. | 2 | The mandates for each long-term component explicitly express long-term objectives and shorter-term downside tolerance. | 19 |

| Specific components of our Fund are explicitly designated to focus on investing for the long-term. | 3 | Our approach to evaluating long-term fund components is meaningfully different from other components. | 20 |

| We have a specific overall allocation policy to implement a long-term orientation in our Fund. | 4 | The investment manager compensation for the long-term fund components has been explicitly designed to reflect the long investment horizon. | 21 |

| We believe that our long-term investing protocols create significant value. | 5 | We (or our managers on our behalf) explicitly integrate environmental and social factors into deciding which corporations we invest in. | 22 |

Table 10: Regional Variations in Long-Horizon Investing Rankings

LONG HORIZON INVESTING

|

+ Response more than 0.5 above mean |

|||||

|

Regional variation from mean response to questions |

Europe |

Canada |

USA |

Asia Australia New Zealand |

All plan Mean Response |

|

We or our managers on our behalf have explicit policies for engaging corporations or other organizations we invest in when we think proactive engagement is warranted. |

|

|

|

|

4.4 |

|

We or our managers on our behalf explicitly integrate environmental and social factors into deciding which corporations we invest in. |

|

|

|

|

4.1 |

|

Specific components of our Fund are explicitly designated to focus on investing for the long-term. |

|

|

|

|

5.5 |

It is tempting to attach considerable weight to the positive correlation between the governance scores and the long-horizon investing scores indicated in Figure 3.xi Does stronger pension governance really lead to a greater emphasis on long-horizon investing? Or does it simply reflect a consistent high/low ranking bias by the survey participants? (i.e., some participants may have a consistently positive ranking bias, while other may have a consistently negative bias). The written participant comments below shed light on how these questions might be answered.

Additional Insights on Long-Horizon Investing from Respondent Comments

In addition to ranking the 22 long-horizon investing statements, survey participants were asked to address the question: “Please feel free to elaborate on any of the rankings you have assigned. We would also like to learn more about your organization’s journey towards long-horizon investing to date, and your intentions over the next three years.”

This is what they told us:

- “…(We have) long term strategic planning, but we are facing regulation that forces us to think short term..”

- “…It is difficult to describe differences in our approach with respect to long-term and short-term investing. Our due diligence processes are consistently applied with a view to longer-term performance.”

- “Really at the start of the journey but progressing fast. … DB funds not always as long-term as they would like to be given de-risking.”

- “In a peer sensitive environment, it is generally difficult to be truly long-term in investing. Even if the current board and investment team take long-term positions, competitive pressures can stand to dominate. In such cases, a change in the board can bring risks of change in approach. Extraction from long-term positions can be very expensive.”

- “The long-term investing belief is now firmly rooted… A lot of work had to be done on policy making, mandate formulation and actually starting long-term mandates. We find it challenging to define a monitoring and guidance framework for long-term investing (we feel we need new "Language" there, Not many people seem to have answers to these questions)…”

- “…competitive advantage accrues to investors able to take a long view. This (led us to) high weightings in illiquid or semi-liquid investments. Returns have mostly been good but … returns to external managers have been much better (fees!) … long-termism did not sufficiently permeate our liquid investments…organized around market index-relative metrics. We are in the process of developing a much more joined-up approach, with …internal investment selection…buy-to-hold and more substantial approach to sustainable ownership.”

- “All our investments, apart from short term liquidity, are invested with a long-term perspective.…We do not believe that the interests of external fund managers are genuinely aligned with ours…”

- “Long-term investing is less about time frame and more about alignment with long-term objectives of the investor and long-term structural trends (e.g. climate change). It is when you invest with an interest in the cashflow-generating potential of the investment over the long-term. It is not a buy and hold strategy. Investors who are permanently invested in equity indices are not long-term investors, even if they have low turnover/ no turnover”

- “…having long term liabilities does not entail a particular – and particularly patient – approach to investment. We may buy assets, that you would think of as “long term” – e.g. infrastructure or forests – but if markets or other developments create a situation where we find that selling is in the better interest of our clients, that is what we will do.”

To us, these comments suggest that the measured statistical correlation between the Survey governance quality rankings and the long-horizon investment quality rankings are likely not to simply reflect survey respondent biases. Plausibly, the comments suggest that better-governed pension funds do indeed ‘think smarter’, and as a result, have more effective long-horizon investment programs.

Part VI: Key Take-Aways from the 2014 Survey Findings

In our view, the survey findings lead to three key conclusions:

- On Governance: while there is some evidence of improvement in the governance of pension organizations since 1997, major concerns about how board members are selected and trained, about the effectiveness of board oversight processes, and about the ability to attract and retain key executive and professional skills remain.

- On Long-Horizon Investing: the comfort with, and the aspirations for the concept of long-horizon investing has yet to be matched with the design and application of an effective suite of implementation strategies that can realize those aspirations.

- On the Relationship between Governance and Long-Horizon Investing: the survey offers plausible evidence of a positive relationship between governance quality and long-horizon investing quality. This relationship is likely not a spurious one.

In short, there is still much work to do to materially strengthen the effectiveness of both the governance and long-horizon investing functions in pension organizations. Likely, better governance also means better long-horizon investing, which in turn likely means higher return investing.xii

Keith Ambachtsheer and John McLaughlin

Endnotes:

- For more information on the FCLT initiative, visit www.FCLT.org.

- From Barton and Wiseman (2014) “Focusing Capital on the Long-Term”, Harvard Business Review, Jan-Feb. Barton and Wiseman also published a follow-up article in the Jan-Feb 2015 issue of the HBR titled “Where Boards Fall Short”.

- O’Barr and Conley (1992) “Fortune and Folly: The Wealth and Power of Institutional Investing”. Irwin Books.

- Keynes (1936) “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money”, Chapter 12. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ambachtsheer, Boice, Ezra, McLaughlin (1995), “Excellence Shortfall in Pension Fund Management: Anatomy of a Problem”, unpublished working paper.

- The studies by Clarke et al. are summarized in (2008) “Best-Practice Pension Fund Governance”. Journal of Asset Management. See also Clapman (2007) “Model Governance Provisions to Support Pension Fund Best-Practice Principles”. Stanford University Law School.

- Clark and Urwin (2008) “Making Pension Boards Work: The Critical Role of Leadership”. Rotman International Journal of Pension Management, Fall.

- Ambachtsheer, Capelle, and Lum (2008) “The Pension Governance Deficit: Still With Us”. Rotman International Journal of Pension Management, Fall.

- BEP6 and BEP7 will be offered February 9-13 and November 30-December 4 in 2015, visit https://www.rotman.utoronto.ca/ProfessionalDevelopment/Executive- Programs/CoursesWorkshops/Programs/Pension-Management.aspx for more information.

- The “Other” category in Table 4 was a mix of multi-employer pension plans, union pension plans, fiduciary managers, and special-purpose organizations such as workers compensation insurers.

- The correlation coefficient is 0.55. Its t-value is 5.9, indicating a high degree of statistical significance.

- See Ambachtsheer (2014) “The Case for Long-Termism”, Rotman International Journal of Pension Management (Fall) for more on the connection between investment performance and long-horizon investing.

KPA Advisory Services Inc.